This is a brain bump of thoughts I’ve noticed as I navigate the complex spheres of tech and education in higher education, especially with the increasing adoption of generative AI in student workflows.

Education + Generative AI

In Spring 2025, I was in a class with 25 other educators ranging from teachers to policy makers to librarians, and many had decades of experience. All of my classmates were working on their PhD in education. Our discussions quickly dissolved into the current impacts of generative AI on education.

In short, our discussions explored the concerns about generative AI. It enables students to outsource their school work to someone else, or thing, without truly learning the material or doing the exercises.

While I agree with their sentiment, I argue that this sentiment towards education/learning is nothing new. For example, various forms of cheating existed, but its reach was limited due to high cost. The main difference now is that the barrier to entry has significantly lowered, but the intent is the same. More on this in the next section.

In response to this increased availability, there’s various stances on generative AI usage in schools. I’ve heard a range of adoption from banned completely to limited usage on assignments to modeled usage via assignments. The decision behind such policies and stances stem from a lot of areas, such as lack of understanding, limited time/resources, skepticism, reluctance, uncertainty, and much more. These were just some of the points of hesitation mentioned by K-12 teachers at the NJ CS Summit in Dec 2024. In education, an industry burdened by layers of bureaucracy and policies, these are all completely valid reasons.

These policies and stances may be made with good intentions in the context of education and learning. Yes, it is a good idea to prevent students from using a tool to give them all the answers to an assignment or test. Yes, it is a good idea to be skeptic and incorporate AI into classrooms without fully understanding the consequences.

However, these uncertainties delay policy making and it affects our students the most. Pre generative AI, there was already a large gap between skills learned in computer science classes versus industry-demanded skills. After wide generative AI adoption, students are woefully under prepared for the growing reliance on generative AI in the post-graduation industry. Proper generative AI usage is a skill, similar to how we were taught to use encyclopedias or search engines in elementary school.

At DevRelCon 2025, nearly all talks parroted the rising demand of AI in engineer workflows, and how they need to move fast to incorporate AI into their educational demos. If educators sit at one end (retroactively responds to industry trends and topics), developer relations professionals sit at the complete opposite end: trailblazers in the software engineering field.

In short, educators need to brace the inevitable adoption of generative AI in schools as matter of when, not if. Instead of debating whether or not to adopt AI, educators instead should focus on the core underlying issue: a student’s mindset towards education and learning.

Why AI usage is a human behavior problem

The entire point of this post is to argue that the current issue in education is not generative AI itself. The technology could’ve been anything like a robot doing your homework; the flavor of the technology does not matter. The core issue is a human behavior problem.

Imagine yourself in 9th grade English class and your teacher assigns 2 chapters per day of Brave New World. The book is dense and jammed full of complex themes, but I’d rather be outside playing with my friends or buying a new outfit for school to impress my friends. So, I use ChatGPT to summarize the required chapters so I know enough to pass the quizzes.

Replace ChatGPT with SparkNotes, and this is exactly what I did in high school. Admittedly, I don’t think I fully read a single assigned book. I didn’t have the motivation to spend the time and energy on this homework task, even if it was assigned. However, I was motivated enough to not fail my classes, so I took the path of least resistance: SparkNotes.

Now that I’m almost 30, I see the value in these books and their complex themes. I’ve picked up Brave New World because it’s relevant to my current life and thoughts. I now have an innate sense of motivation to spend the time and energy to do this task, even without a grade looming over my head.

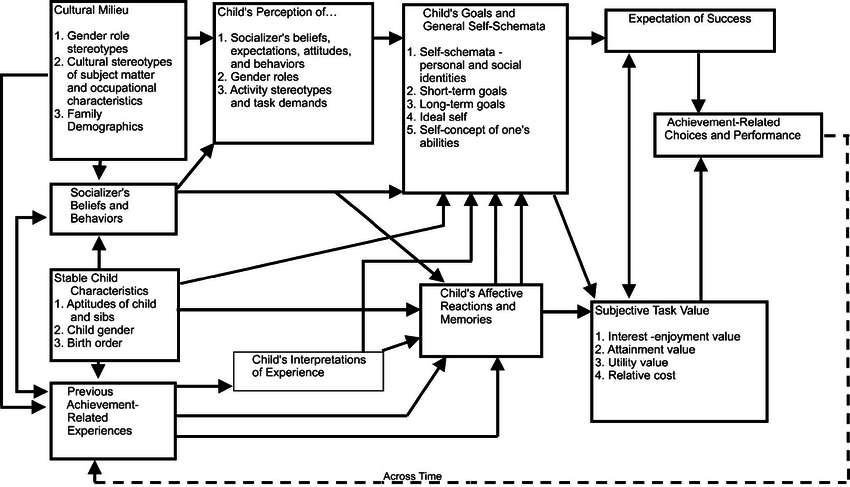

In this example, the common themes to highlight are motivation, relevance, and value. Tangential themes can be seen on the bottom-right side of Eccles’s (1983) expectancy-value theory of motivation under “Subjective Task Value”.

“Achievement-related choices and performance” are influenced by both a person’s “expectation of success” and their “subjective-task value”. In the example, my expectation of success was normal (I knew I had the ability to sit down and read the book), but I saw little to no value in the task. Thus, I outsourced the given homework task.

It’s worth noting the opposite can also be true where a student finds value, but they do not believe they can succeed. I’ve seen plenty of students who recognize the value in learning how to code, but don’t believe in their success, so they rely on tutors or end up on ChatGPT for a basic programming assignment.

Breaking out of the example, most students likely follow the same train of thought: outsource any learning that’s not valuable to me or likely to succeed. Before generative AI, such students would likely resort to various cheating tactics with varying levels of entry, complication, difficulty, and risk. Students would weigh the risk versus reward and decide the best path forward.

Now with generative AI, all of the factors to weigh have significantly decreased in weight: the barrier to entry is nearly non-existent; complication and difficulty are lowered as tech companies exploit usage by intentionally making it as easy as possible; risk is diminished from the generative AI’s increasing ability to tune its models towards believability.

In short, the flavor of technology does not matter. The way a student chooses to use a tool is dependent on a student’s innate “achievement-related choices and performance”, which is reliant on their “subjective task value” and “expectation of success”. If either component is missing when approaching a homework task, then they’ll take the path of least resistance.

Students will either not do the assignment or outsource the work.

What can educators do?

Tweaking assignments and assessments to increase value and improve a student’s perception of success is the obvious next path. However, doing so takes a lot of time, resources, and energy from both educators and students. Many educators have already expressed expressed they are strapped for all three.

So in short, I don’t know. A lot of conversations have diverged to changing the education and assessment system, but it takes a long time. Generative AI is making an impact on our students now. Lots of educational institutions have released statements regarding their approach to AI. I’d recommend making your own assessments based on your unique situation.

Regardless, the one thing I can confidently say is: AI cannot replace the human component of educators and education.

The current models of generative AI are not “thinking.” At its core, they are prediction models; they predict the next most likely word in the sentence based on its incredibly vast training data and user input.

A recent article discussed the capacities of generative AI and its limitations, especially in the context of tutoring- I’d recommend reading it. A text-based AI cannot replace the subtle body language and facial expressions, signaling the student is completely lost. Educators need to skillfully reassess how they approach the learning experience, in concert with the student’s body language.

To close, I’m working on a few papers related to education and generative AI. I can’t wait to share my new findings on the ever changing AI industry and its impact on education.

Leave a comment