“Boys are just naturally better at math.” “Girls prefer reading and writing over science.” “Computer science is for guys who like video games.”

Sound familiar? These seemingly innocent comments reflect deeply ingrained stereotypes that start shaping academic trajectories much earlier than we think. By middle school, these stereotypes don’t just influence what subjects girls think they’re “good at”—they fundamentally impact whether girls feel like they belong in STEM at all.

After diving deep into the research on gender stereotypes in STEM education, I discovered that middle school represents a critical intervention point. Here’s why this timing matters and what we can do about it.

This blog serves as a summary of a term paper I wrote for my Ed.M. in Educational Psychology; you can find the full paper here.

The Timing Problem: Why Middle School is Vital

Middle school sits at a unique intersection in academic development. It’s too late for elementary school approaches (when stereotypes are just forming), but not too late for intervention before high school course selections. Unsurprisingly, high school course selection has a larger-than-expected long-term impact on academic trajectories in university and college.

Consider the math pathway: a student who doesn’t take algebra in middle school faces an uphill battle to reach calculus by senior year high school. Since higher-level mathematics is essentially required for most STEM majors, these early decisions have cascading effects on college and future career options.

But here’s what makes middle school particularly challenging: it’s when academic competitiveness ramps up significantly. Students become hyper-aware of peer culture and social expectations. The combination of puberty, increased grade emphasis, and social pressure creates the perfect storm for stereotype reinforcement.

The Two Types of Gender Stereotypes That Matter

Research identifies two distinct but interconnected types of stereotypes affecting middle school girls:

1. Interest-Based Stereotypes: “Girls Don’t Like STEM”

These shape perceptions about who belongs in STEM spaces. Examples include:

- Classroom decorations featuring stereotypically masculine items (Star Wars posters, computer parts)

- Media representations showing STEM fields as male-dominated

- Implicit messaging that “other girls don’t like science, so you shouldn’t either”

The Impact: When girls walk into a computer science classroom decorated with video game posters, they receive an immediate signal that this space wasn’t designed for them.

2. Ability-Based Stereotypes: “Girls Aren’t Good at Math”

These shape beliefs about natural talent and capability. The research shows:

- Children as young as 2nd grade associate “boys” with “math ability” versus “girls” with “spelling”

- In group science activities, boys typically assume leadership roles while girls take supportive positions

- Girls are often socialized into “good student” behaviors (following directions, avoiding risks), which don’t align with open-ended STEM exploration

The Impact: Girls internalize messages about their mathematical abilities, leading them to avoid challenging courses even when their actual performance equals that of their male peers.

The Belonging Framework: Why Feeling Like You Fit In Matters

Traditional approaches focus on interest and ability, but recent research highlights a crucial third factor: belonging—the sense that you fit in with the people, materials, and activities in an environment. Belonging operates through four interconnected dimensions:

- Competence

- Do I have the skills to connect with others in this space?

- When girls endorse ability-based stereotypes, they perceive themselves as having fewer relevant skills, making it harder to relate to classmates and build confidence in STEM activities.

- Opportunity

- Am I given chances to engage meaningfully?

- Girls are often socialized into passive, supportive roles rather than leadership positions in group work, reducing their opportunities to direct their own learning in open-ended experiments.

- Motivation

- Do I want to be part of this community?

- If STEM doesn’t align with a girl’s future plans or values, she may lack the motivation to pursue advanced coursework, even if she meets the competence and opportunity criteria.

- Perception

- How do I interpret my experiences in this space?

- This may be the most stereotype-influenced dimension. Girls might purposefully underperform or avoid leadership roles to conform to social expectations and avoid peer ostracism.

The Critical Point: All four dimensions must be satisfied for genuine belonging. A girl might have the competence and opportunity to succeed in STEM but still feel like an outsider if the motivation and perception pieces are missing.

The Expectancy-Value Connection

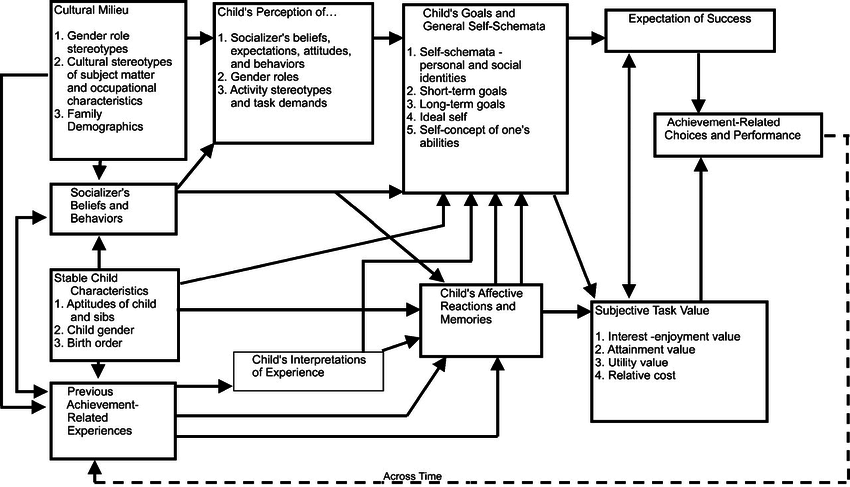

The effects of stereotypes operate through Eccles’s (1983) expectancy-value theory of motivation. This framework suggests that achievement-related choices depend on two core factors:

- Expectation of success: “Can I do well in this subject?”

- Value placed on the task: “Is this worth my time and effort?”

Stereotypes attack both components:

- Ability-based stereotypes lower expectations of success

- Interest-based stereotypes reduce the perceived value of STEM engagement

The result? Girls make rational decisions to avoid STEM based on distorted information about their capabilities and the field’s relevance to their lives. What starts as subtle stereotype exposure in middle school creates compound effects:

- Middle School: Girls avoid advanced math courses, reducing STEM preparation

- High School: Limited course options due to inadequate prerequisites

- College: Fewer STEM majors among qualified female students

- Career: Persistent gender gaps in STEM fields

The research shows that cognitive abilities between girls and boys are empirically equal—sociocultural factors, not biological differences, drive these career patterns.

What Actually Works: Evidence-Based Interventions

Based on the belonging framework, effective interventions should address all four dimensions:

- Targeting Competence: Growth Mindset Training

- Teach girls about theories of intelligence and the growth mindset. When students understand that intelligence is malleable rather than fixed, they’re more likely to persist through challenges and take on advanced coursework.

- Creating Opportunities: Structured Group Work

- Instead of letting group dynamics naturally emerge (which often default to stereotypical patterns), explicitly assign roles and responsibilities. Give girls specific opportunities to lead and direct their learning in open-ended experiments.

- Building Motivation: Connecting STEM to Personal Values and Interests

- Emphasize how STEM connects to topics girls already care about. Show applications in medicine, environmental science, social justice, or other areas that align with their values and future goals.

- Shifting Perceptions: Environmental Changes

- Remove stereotypically masculine decorations from STEM classrooms. Replace Star Wars posters and computer parts with plants, nature pictures, and other gender-neutral items that send inclusive messages.

Beyond Individual Solutions: Systemic Change

While individual interventions help, addressing gender stereotypes in STEM requires systemic change:

- For Educators: Professional development on recognizing and counteracting implicit bias in classroom environments and interactions

- For Parents: Awareness of how everyday comments and purchases (even toy choices) reinforce or challenge stereotypes

- For Policymakers: Curriculum standards that explicitly address stereotype awareness and inclusive STEM education

- For Researchers: Continued investigation into the belonging framework and its applications in educational settings

The gender gap in STEM isn’t about ability—it’s about belonging. When we understand how stereotypes operate through the four dimensions of belonging, we can design more effective interventions.

Middle school represents our best opportunity to interrupt stereotype-driven trajectories. By addressing competence, opportunity, motivation, and perception simultaneously, we can help girls see themselves as natural members of STEM communities.

The goal isn’t just gender parity in STEM fields, though that also matters. It’s about ensuring a person’s academic and career choices reflect genuine interests and abilities rather than distorted messages about who belongs where.

When we create environments where all students feel like they belong, we don’t just help individuals—we strengthen the entire field by harnessing the full range of human talent and perspective.

This analysis is based on research from my graduate coursework exploring the intersection of educational psychology and STEM equity. The findings have significant implications for how we design learning environments and support student development during critical transition periods.

This blog serves as a summary of a term paper I wrote; you can find the full paper here.

Key References:

- Allen, K. A., et al. (2021). Belonging: A review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Australian Journal of Psychology.

- Master, A., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2020). Cultural stereotypes and sense of belonging contribute to gender gaps in STEM. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology.

- Tang, D., et al. (2024). Longitudinal stability and change across a year in children’s gender stereotypes about four different STEM fields. Developmental Psychology.

Leave a comment